Current Research

The research in the Temperton Lab is focused on understanding the impact and evolution of host-virus interactions, and their role in shaping microbial communities in both environmental, aquaculture and clinical settings. Currently this falls into five main research areas:

1. The Citizen Phage Library

In response to the growing global threat of antimicrobial resistance, we established the Citizen Phage Library to provide clinicians with suitable phages to treat drug-resistant bacterial infections. Through our citizen science program, we are now one of the largest phage biobanks in the world. We are developing novel approaches to isolation, phage engineering, cell-free phage rebooting and advanced cocktail design.

2. Developing long-read sequencing technology for improved viral metagenomics

In recent years, our understanding of viral ecology in marine and soils systems has been dramatically enhanced by the development of protocols for robust viral metagenomic sequencing and analysis. This work has shown that viruses are major drivers of global carbon biogeochemical cycles, horizontal gene transfer and carbon transport from the surface to the deep ocean. However, short-read methods fail to assemble important and extremely abundant members of viral communities, such as viruses infecting the globally dominant Pelagibacterales. It is hypothesised that the high abundance and microdiversity in these viral populations challenge resolution of De Bruijn Graph assembly, leading to highly fragmented genomes. We recently developed methods to overcome this using long-read metagenomes on the Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencer. This new method of sequencing captures abundant and diverse viral populations previously missed by short reads. Furthermore, the long reads enable us to explore and better understand the role of viral hypervariable regions in niche-adaptation.

3. Quantifying the impact of host-virus interactions on carbon flux in the Open Ocean

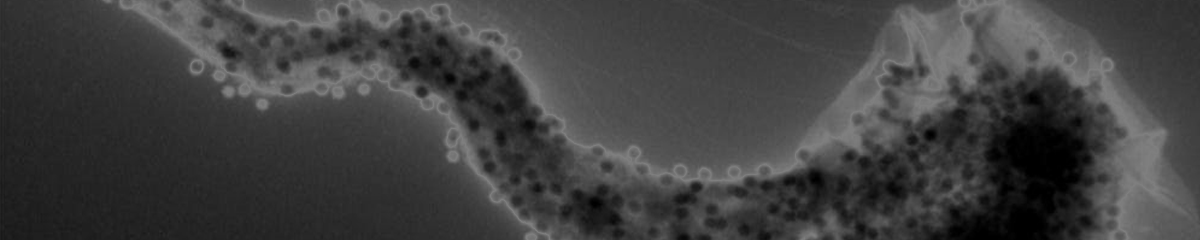

Viruses are the most abundant organisms on Earth, and profoundly impact nutrient cycling in the oceans. They are predicted to kill around 1 in 3 cells every day in the oceans, releasing intracellular dissolved organic carbon into the water for use by the surviving community, and causing cell debris to sink into the deep ocean. Phages are estimated to be responsible for ~150 Gt of carbon flux in the oceans every year. As part of the BIOS-SCOPE project, we are investigating how viral predation impacts carbon availability and sequestration in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre.

4. Understanding how genome minimalism impacts host-virus interactions

After 100 years of phage research, it is understood that during early infection, viruses hijack their host metabolism, either by reconfiguring host RNA polymerase, or encoding their own viral version, ultimately rewiring metabolism to favour the production of new viral progeny. In doing so an infected cell presents a dramatically different phenotype than a non-infected cell, altering its interactions with available substrates and its microbial neighbours. However, all research into mechanisms of viral hijacking have used fast-growing laboratory stalwarts such as E. coli and Pseudomonas. These R-strategists are replete with complex transcriptional and translational control mechanisms, and their infecting phages demonstrate highly orchestrated successions of phage proteins to reconfigure the host metabolism. However in natural nutrient-limited environments, including soils and much of the global ocean surface, fast-growing taxa with large genomes encoding complex regulatory mechanisms are the exception, rather than the rule. Such communities are instead dominated by bacteria with highly streamlined genomes that favour constitutive gene expression, regulation of metabolic pathways through enzyme kinetics and extensive use of riboswitches. Slow growth rates and small cell sizes further constrain the available options for arms-race dynamics between viruses and hosts. In our lab, we perform experimental co-evolution experiments of streamlined bacteria such as SAR11 and OM43 to investigate the impact of genome minimalism on host-virus interactions.

5. Identifying the role of host-virus interactions in aquaculture species.

Aquaculture currently provides over half of all fish for human consumption. With global populations set to rise to 9.7 billion by 2050, aquaculture is of major importance to food security, particularly in low-income food-deficit countries. Presently, disease acts as the major constraint to aquaculture productivity, exacerbated by over-stocking, poor water quality and the emergence of new pathogens with global reach thanks to international trade. Animal-associated microbiomes are understood to be an integral component of animal health, with shifts in microbial communities associated with positive or negative health outcomes. Our lab aims to better understand the role of viruses in microbiome stability and disturbance during fish development and disease outbreaks, and the impact of lysogeny on horizontal gene transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes. We are also developing novel field-based sequencing techniques for real-time analysis of pathogenic viral outbreaks such as Tilapia lake virus, in collaboration with WorldFish and Cefas.